No Man is an Island

Established in 1979 as the first hospice in Africa, Island Hospice and Healthcare (Island) was born out of the recognition that there was need for direct home-based palliative care for those with life threatening illnesses and their families, as well as a comprehensive bereavement service.

In 2014, Island rebranded in Zimbabwe and engaged the services of several local photographers to document their work, telling the stories of some of their past staff members and clients. This is a small selection of images from the project.

Rhona Martin, currently a board member at Island Hospice, has worked with the charity since 1984 when there was only one doctor and one nurse. She says one of the most difficult things has been watching Island expand and then contract due to the economic situation in Zimbabwe. For Rhona, Island’s role is to help people find a balance between talking about death and helping them to live.

Rhona Martin, currently a board member at Island Hospice, has worked with the charity since 1984 when there was only one doctor and one nurse. She says one of the most difficult things has been watching Island expand and then contract due to the economic situation in Zimbabwe. For Rhona, Island’s role is to help people find a balance between talking about death and helping them to live.

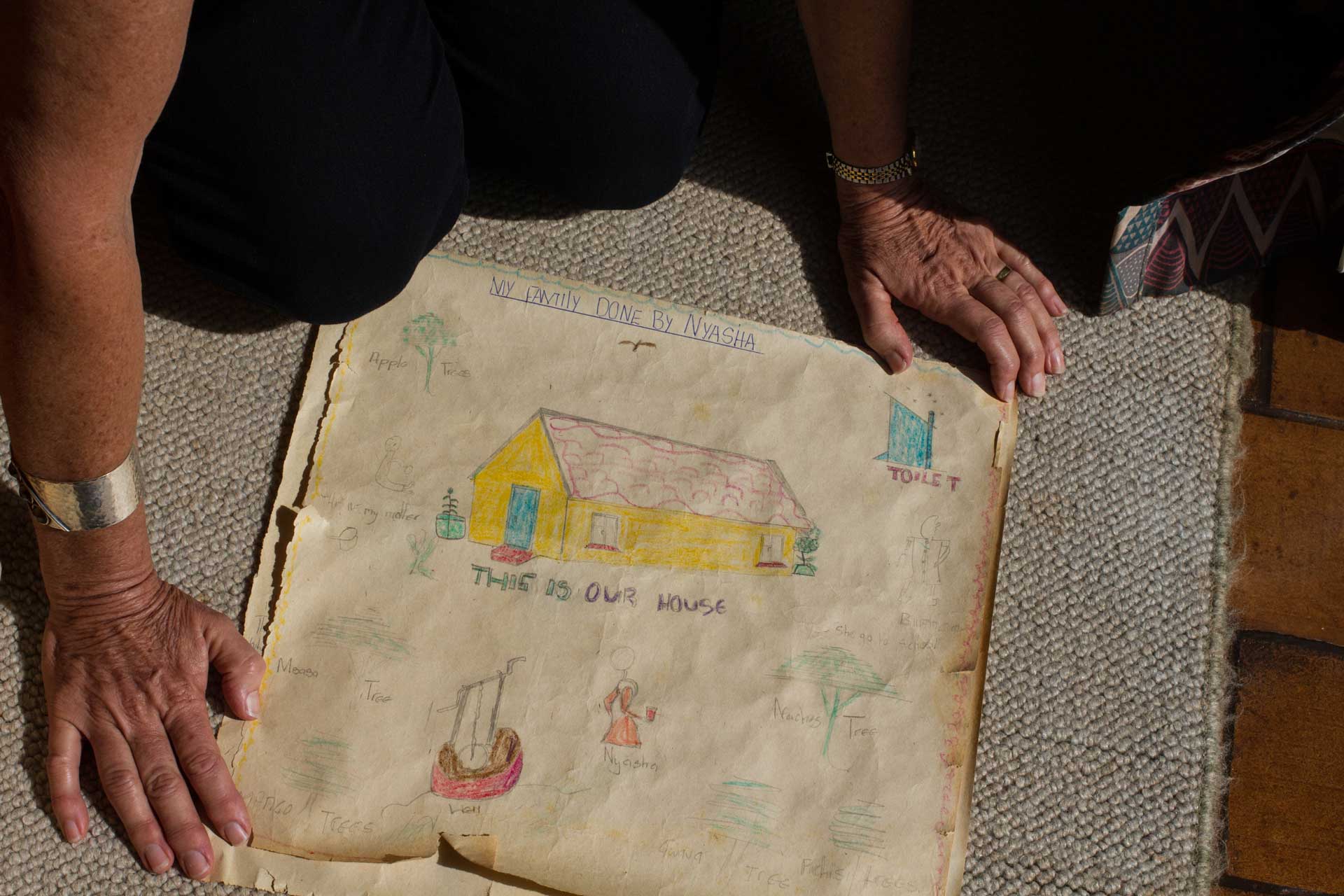

In particular, Rhona loved working with bereaved children, whom she says are so smart at finding whatever it is that will help them, if they are only given the opportunity. But she also says, “You can’t help everyone…some people’s lives are hard and sad and it’s not our brief to change that. Sometimes it’s too hard.”

In particular, Rhona loved working with bereaved children, whom she says are so smart at finding whatever it is that will help them, if they are only given the opportunity. But she also says, “You can’t help everyone…some people’s lives are hard and sad and it’s not our brief to change that. Sometimes it’s too hard.”

Pauline Blanchard-Sims is about to turn 90. She worked as a nurse for Island Hospice since 1981 doing palliative care for terminally ill patients. She said, “My first ever visit…I was so nervous, I had finished training and I was sent out to see my first patient, but I think it went very well because she was so delighted to see me, to know that someone would be coming… the best part of the job for me was going to these patients and finding that they were just so in need of someone to visit them…[they] were so thrilled to have me there, to have someone with them when they were dying.”

Pauline Blanchard-Sims is about to turn 90. She worked as a nurse for Island Hospice since 1981 doing palliative care for terminally ill patients. She said, “My first ever visit…I was so nervous, I had finished training and I was sent out to see my first patient, but I think it went very well because she was so delighted to see me, to know that someone would be coming… the best part of the job for me was going to these patients and finding that they were just so in need of someone to visit them…[they] were so thrilled to have me there, to have someone with them when they were dying.”

Jane Soper is a voluntary caregiver/counsellor at Island. She believes in person-centred therapy, described above, which gives a person a safe space to speak about painful things. “I can sit with somebody and offer something they’re unlikely to get from friends and family.”

Jane Soper is a voluntary caregiver/counsellor at Island. She believes in person-centred therapy, described above, which gives a person a safe space to speak about painful things. “I can sit with somebody and offer something they’re unlikely to get from friends and family.”

Jane says she was brought up in a culture that struggled to accept or talk about difficult emotions, which may be why she thinks it is so important to learn how to accept sadness. “My role is to help without interfering…I’m there to listen, not give advice or make things better.”

Jane says she was brought up in a culture that struggled to accept or talk about difficult emotions, which may be why she thinks it is so important to learn how to accept sadness. “My role is to help without interfering…I’m there to listen, not give advice or make things better.”

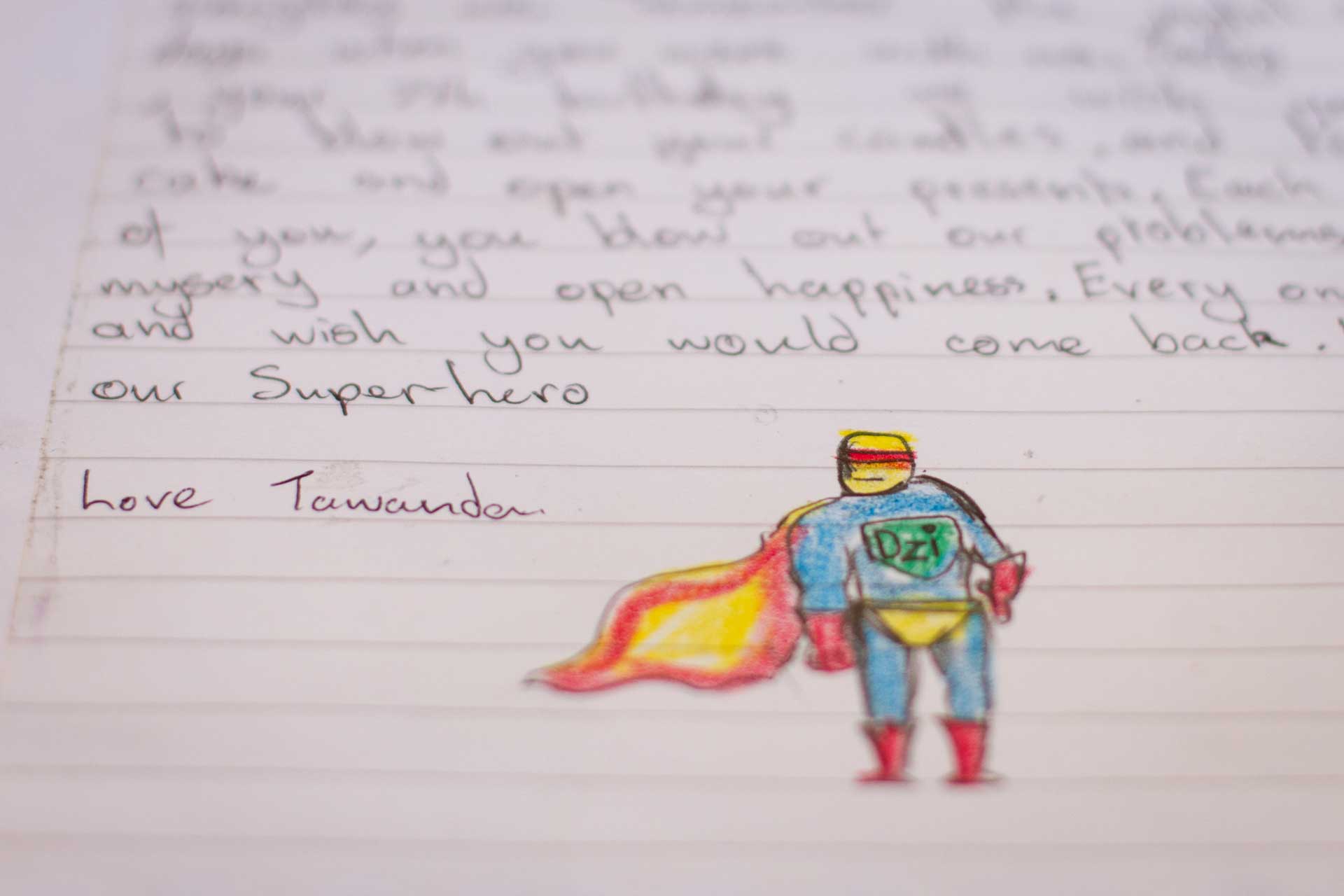

Admire and Kundai Masenda lost their second son Munyaradzi ‘Dzi’ in a car accident in 2009. He was six years old. For them, Island was a place to talk about Dzi, especially when so many people around them didn’t know how to address the subject of his death. Five years later, Dzi is still part of the Masenda’s daily life – his pictures and artwork adorn the refrigerator, his brother, Shingai, has kept their room exactly as it was, and they talk about their ‘superhero’ at every opportunity they get.

Admire and Kundai Masenda lost their second son Munyaradzi ‘Dzi’ in a car accident in 2009. He was six years old. For them, Island was a place to talk about Dzi, especially when so many people around them didn’t know how to address the subject of his death. Five years later, Dzi is still part of the Masenda’s daily life – his pictures and artwork adorn the refrigerator, his brother, Shingai, has kept their room exactly as it was, and they talk about their ‘superhero’ at every opportunity they get.

Kundai, here pictured with her older son, Shingai, remembered: “I was crying and really struggling and Shingai said to me, ‘Mom, you shouldn’t be worried about Dzi, you should rather be worrying about yourself so that you can make sure you see him in Heaven.’ I thought to myself, who is the mother and who is the child?”

Kundai, here pictured with her older son, Shingai, remembered: “I was crying and really struggling and Shingai said to me, ‘Mom, you shouldn’t be worried about Dzi, you should rather be worrying about yourself so that you can make sure you see him in Heaven.’ I thought to myself, who is the mother and who is the child?”

“I remember his enthusiasm for life and how he would run out to greet me when I came home from work,” says Admire. “He was like a 40-year-old with the number of lives he had already touched,” remembers Kundai, “he really lived a full 6 years.”

“I remember his enthusiasm for life and how he would run out to greet me when I came home from work,” says Admire. “He was like a 40-year-old with the number of lives he had already touched,” remembers Kundai, “he really lived a full 6 years.”