The Cycle

Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe, is situated upstream from its water supply, Lake Chivero, and sits in its own catchment area. Grey water from homes and industries flows through its polluted urban rivers back into the drinking water. The water treatment process used to enable a sustainable cycle in which Harare’s residents literally drank their own bathwater.

However, the extension of water supply and sanitation infrastructure has not been able to keep up with the urban population growth. The water system was designed for a population of 250, 000 – less than one-tenth of the current population.

A lack of investment in water infrastructure since the 1970s, and the collapse of the water purification process in particular, has seriously impacted the health, safety, dignity and livelihoods of Harare’s residents.

As a result, in Harare water has become a valuable commodity. Although the entire city has been affected, the iconic phrase from Mark Reisner’s Cadillac Desert, “water flows upstream towards power and money,” is quite literally true in Harare where the wealthier suburbs are located at the apex of the water supply cycle. These residents can afford to dig their own boreholes or buy water. But for those ‘living downstream’ in the poorer high-density suburbs, which are totally dependent on the municipality, Harare’s water system forms a potentially deadly cycle for which a viable solution is yet to be found.

Although The Cycle tells the story of Harare, its intention is to create awareness about the need for urban water management in cities around the world. This work was completed for the 2012 Media and Advocacy Photography Mentorship funded by the Market Photo Workshop and mentored by photojournalist Jonathan Torgovnik.

All images © Davina Jogi/MPW

Smoke from cooking fires rises above Dzivarasekwa high density suburb in Harare, Zimbabwe on a winter's evening as residents spill into the street. Harare's high-density suburbs are too overcrowded for the existing infrastructure to support. One homeowner told me, “We are living like mouse I can say, 15 people, some in the kitchen, in the dining, it is mass living.” Her family had been disconnected for owing US$1300 in water bills.

Smoke from cooking fires rises above Dzivarasekwa high density suburb in Harare, Zimbabwe on a winter's evening as residents spill into the street. Harare's high-density suburbs are too overcrowded for the existing infrastructure to support. One homeowner told me, “We are living like mouse I can say, 15 people, some in the kitchen, in the dining, it is mass living.” Her family had been disconnected for owing US$1300 in water bills.

Nigel, 7, baths in a basin at his grandmother's home in Mabvuku. The basin is placed in the toilet, which has not had running water since Nigel was born. The family gets water from a rainwater storage tank and a nearby borehole. Mabvuku is situated on the extreme eastern side of Harare, as far away from the water supply as possible, so water has always been a problem. Ultimately, where you live in Harare and how much you earn determines the quality and quantity of water you receive.

Nigel, 7, baths in a basin at his grandmother's home in Mabvuku. The basin is placed in the toilet, which has not had running water since Nigel was born. The family gets water from a rainwater storage tank and a nearby borehole. Mabvuku is situated on the extreme eastern side of Harare, as far away from the water supply as possible, so water has always been a problem. Ultimately, where you live in Harare and how much you earn determines the quality and quantity of water you receive.

A woman and her grandchild are reflected in a 'mughodi' - a shallow well dug into the drainage ditch in Dzivaresekwa. Such wells are often polluted by storm water run-off and broken sewer connections because they are so shallow.

A woman and her grandchild are reflected in a 'mughodi' - a shallow well dug into the drainage ditch in Dzivaresekwa. Such wells are often polluted by storm water run-off and broken sewer connections because they are so shallow.

A house in Northwood with a swimming pool full of municipal water.

A house in Northwood with a swimming pool full of municipal water.

A member of Dandaro Trust works in their garden plot, which provides much needed nutrition to its HIV positive members in Mabvuku. It is estimated that partly due to the economic meltdown, at least 50% of the city’s 1000km2 land area is used for informal urban agriculture. The majority of farmers use chemical fertilizers and cultivate near streams and wetlands, which leads to water pollution from run-off.

A member of Dandaro Trust works in their garden plot, which provides much needed nutrition to its HIV positive members in Mabvuku. It is estimated that partly due to the economic meltdown, at least 50% of the city’s 1000km2 land area is used for informal urban agriculture. The majority of farmers use chemical fertilizers and cultivate near streams and wetlands, which leads to water pollution from run-off.

An HIV positive woman who contracted typhoid in 2012 and has subsequently suffered from recurring stomach problems. As of May 2, 2012, a total of 4,185 suspected cases of typhoid fever had been identified in Harare . It eventually petered out thanks to the onset of winter.

An HIV positive woman who contracted typhoid in 2012 and has subsequently suffered from recurring stomach problems. As of May 2, 2012, a total of 4,185 suspected cases of typhoid fever had been identified in Harare . It eventually petered out thanks to the onset of winter.

A girl carries water from a public borehole in a high-density area. There is a misconception that borehole water is cleaner than tap water because it comes from underground. In a 2011 study done in Dzivaresekwa, researchers found E.coli in two out of six boreholes and all seven shallow wells they tested, signalling fecal contamination.

A girl carries water from a public borehole in a high-density area. There is a misconception that borehole water is cleaner than tap water because it comes from underground. In a 2011 study done in Dzivaresekwa, researchers found E.coli in two out of six boreholes and all seven shallow wells they tested, signalling fecal contamination.

A woman holds a photograph of her husband, who died in the cholera epidemic in 2008. In 2011, all seven members of her family got typhoid from the municipal water but they continue to drink it without treatment as they dislike the taste of the chlorine tablets.

A woman holds a photograph of her husband, who died in the cholera epidemic in 2008. In 2011, all seven members of her family got typhoid from the municipal water but they continue to drink it without treatment as they dislike the taste of the chlorine tablets.

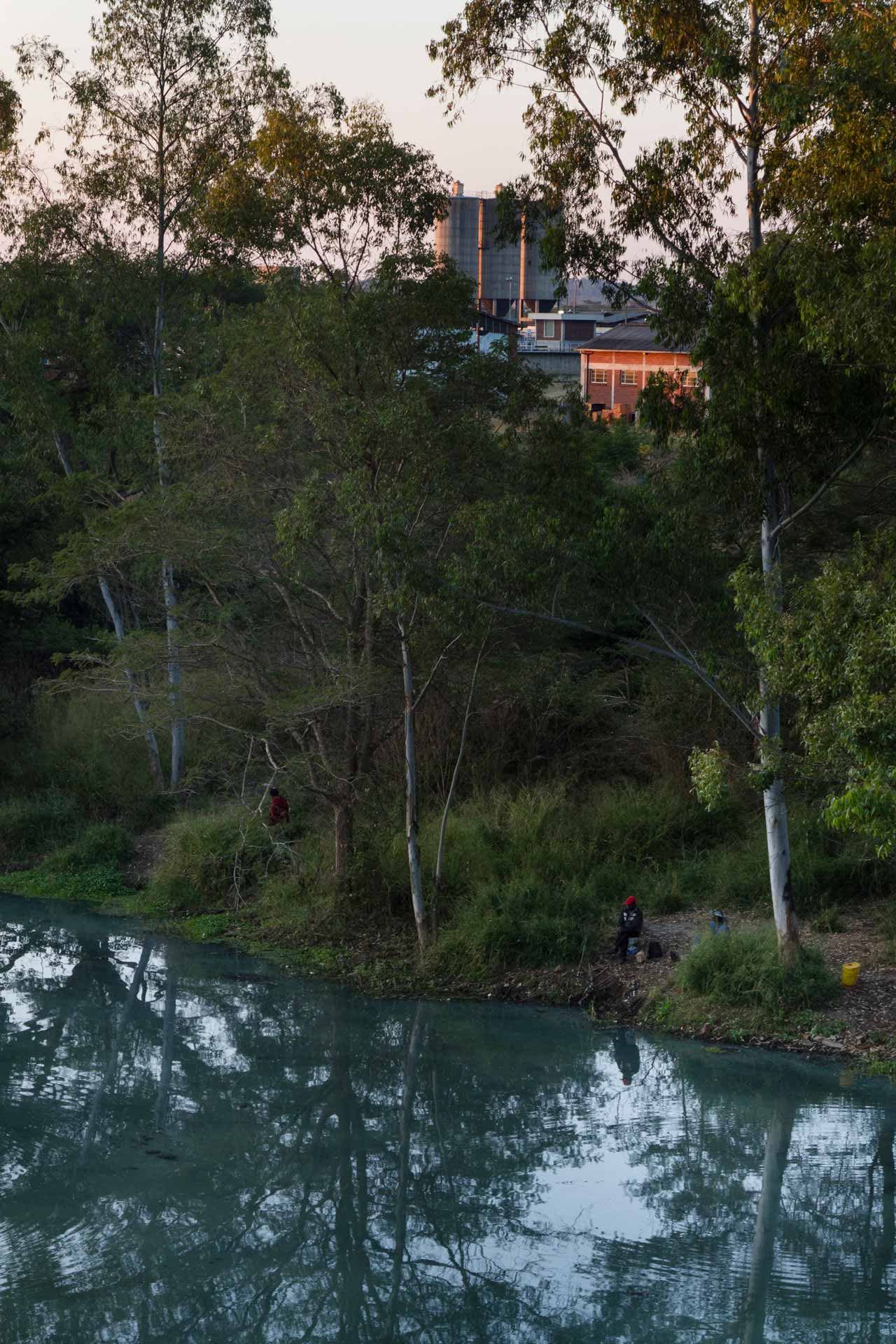

Cloudy blue water below Lake Chivero's spillway indicates the presence of blue-green algae in the water. Built in 1952 and situated downstream from the city, water from Lake Chivero is treated at Morton Jaffrey Water Treatment Works (seen in the background) and piped across Harare before returning to the Lake as sewage effluent through urban rivers. The lake is highly polluted and the dense clouds of blue-green algae impede water purification and discharge toxins that are not removed in the normal water treatment process. Since Harare city sits within its own water catchment area, heavy metals, pesticides and raw sewage all contribute to Lake Chivero’s heavy pollution. Yet the lake remains Harare’s primary source of drinking water and continues to support an informal fishing industry.

Cloudy blue water below Lake Chivero's spillway indicates the presence of blue-green algae in the water. Built in 1952 and situated downstream from the city, water from Lake Chivero is treated at Morton Jaffrey Water Treatment Works (seen in the background) and piped across Harare before returning to the Lake as sewage effluent through urban rivers. The lake is highly polluted and the dense clouds of blue-green algae impede water purification and discharge toxins that are not removed in the normal water treatment process. Since Harare city sits within its own water catchment area, heavy metals, pesticides and raw sewage all contribute to Lake Chivero’s heavy pollution. Yet the lake remains Harare’s primary source of drinking water and continues to support an informal fishing industry.

A family watches as a borehole is dug in their backyard. Harare's residents have always had boreholes, usually to assist during the dry months but the lack of water being supplied by the city has seen a dramatic increase in the number of boreholes being sunk. In the past, it was normal to drill between 20 – 50 m to get to groundwater but, in some parts of Harare people are now drilling 150 m before they reach water. The prohibitive cost (about US$60 per drilled metre) makes borehole water an option only for the wealthy.

A family watches as a borehole is dug in their backyard. Harare's residents have always had boreholes, usually to assist during the dry months but the lack of water being supplied by the city has seen a dramatic increase in the number of boreholes being sunk. In the past, it was normal to drill between 20 – 50 m to get to groundwater but, in some parts of Harare people are now drilling 150 m before they reach water. The prohibitive cost (about US$60 per drilled metre) makes borehole water an option only for the wealthy.

In Borrowdale, a private water company employee transfers water from a storage tank to a truck. The issue of private water supply has become controversial, as those who live next door to suppliers have discovered, they are slowly drying up the reserve of ground water by using generators to pump huge quantities of water 24 hours a day.

In Borrowdale, a private water company employee transfers water from a storage tank to a truck. The issue of private water supply has become controversial, as those who live next door to suppliers have discovered, they are slowly drying up the reserve of ground water by using generators to pump huge quantities of water 24 hours a day.

Reward Njenje, from the Dzivaresekwa Conservation Environment Trust, checks a tank that is used to irrigate their garden beds. The Trust was set up to encourage sustainable community development in Dzivaresekwa and tries to lead by example with urban agriculture, water conservation and waste recycling projects.

Reward Njenje, from the Dzivaresekwa Conservation Environment Trust, checks a tank that is used to irrigate their garden beds. The Trust was set up to encourage sustainable community development in Dzivaresekwa and tries to lead by example with urban agriculture, water conservation and waste recycling projects.

Members of the Combine Harare Residents' Association (CHRA) meet to discuss the challenges they are facing in regards to service delivery. Mired in debt the Zimbabwe government and most city councils have struggled to support the nation's aging infrastructure leaving communities without regular services including electricity, water and rubbish collection

Members of the Combine Harare Residents' Association (CHRA) meet to discuss the challenges they are facing in regards to service delivery. Mired in debt the Zimbabwe government and most city councils have struggled to support the nation's aging infrastructure leaving communities without regular services including electricity, water and rubbish collection

On a hill in Dzivaresekwa, an empty water reservoir is not useful for anything except as a place for prayer. Holy water (muteuro), used for healing and baptism has special significance for the groups of Apostolic sects that dot every available open space in Harare. Many of them choose to worship near rivers and dams, or at reservoirs, which retain their symbolic link to water despite being practically useless.

On a hill in Dzivaresekwa, an empty water reservoir is not useful for anything except as a place for prayer. Holy water (muteuro), used for healing and baptism has special significance for the groups of Apostolic sects that dot every available open space in Harare. Many of them choose to worship near rivers and dams, or at reservoirs, which retain their symbolic link to water despite being practically useless.

Women wash clothes at a leaking municipal tap that constantly pours water. Harare City is only able to supply only about half of its water requirements and of that amount, at least 40% is being lost as non-revenue water. Some of the water leakages occur underground but many of Harare’s residents are managing to acquire revenue free water from loose connections on street level.

Women wash clothes at a leaking municipal tap that constantly pours water. Harare City is only able to supply only about half of its water requirements and of that amount, at least 40% is being lost as non-revenue water. Some of the water leakages occur underground but many of Harare’s residents are managing to acquire revenue free water from loose connections on street level.

Gertrude Sande washes her family's clothes by hand. Detergents and phosphates in laundry soaps stimulate the growth of algae that leads to the death of aquatic life in rivers and lakes. In Harare, the widespread use of such laundry detergents has had a definite impact on the city's water courses.

Gertrude Sande washes her family's clothes by hand. Detergents and phosphates in laundry soaps stimulate the growth of algae that leads to the death of aquatic life in rivers and lakes. In Harare, the widespread use of such laundry detergents has had a definite impact on the city's water courses.

Domestic workers in one of Harare’s wealthy residential suburbs leave buckets near the supply point for a private water company in the hopes that they will be filled with the left over water that remains in the pipe once they have filled their trucks.

Domestic workers in one of Harare’s wealthy residential suburbs leave buckets near the supply point for a private water company in the hopes that they will be filled with the left over water that remains in the pipe once they have filled their trucks.

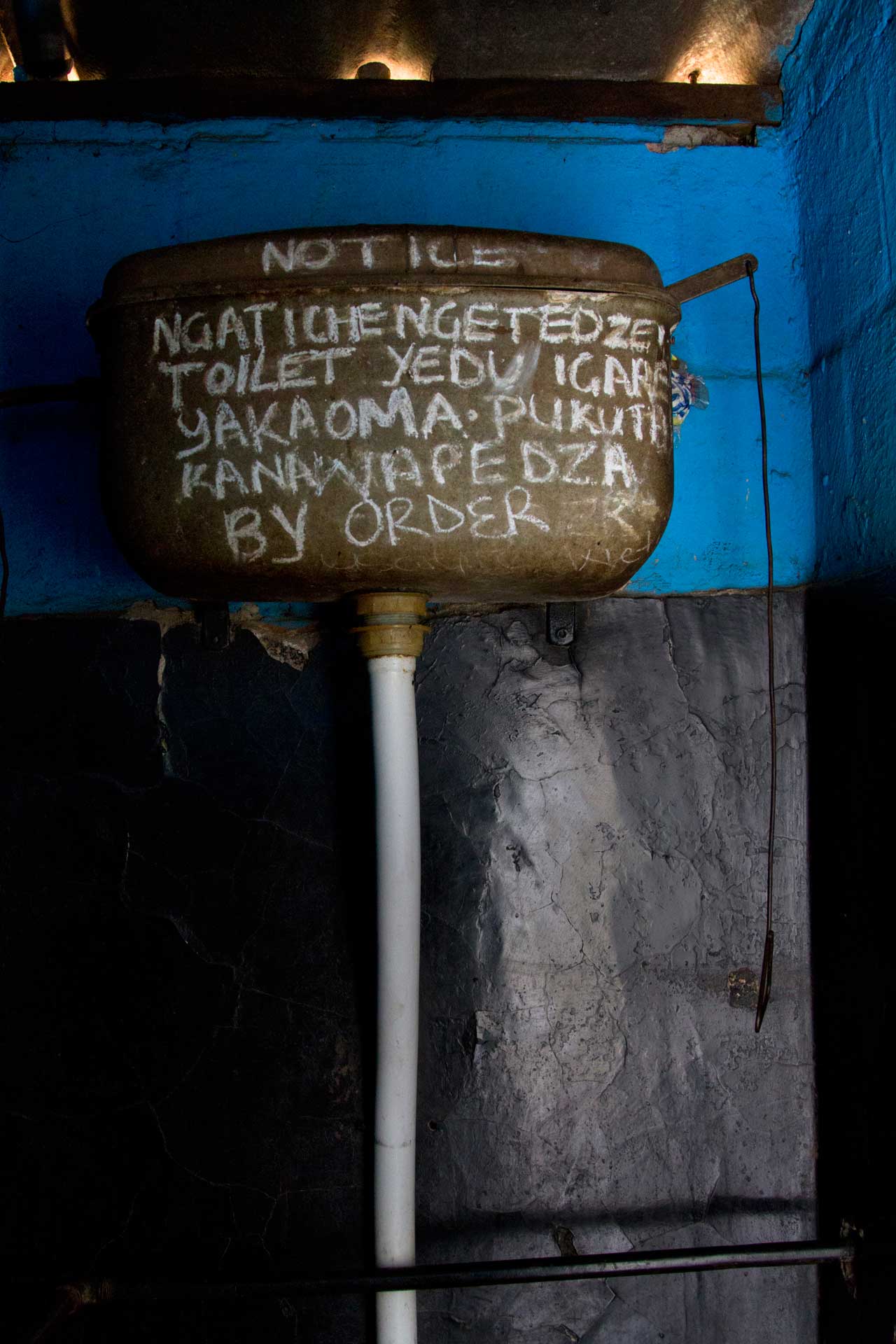

Harare was once unique among African cities for having an exceptionally high number of flush toilets connected to a sewer network. Now, because of severe water cuts and low pressure, this toilet in Dzivaresekwa has no water. Instead grey water is reused and poured down as a flushing mechanism. And because of the growing populations in high-density areas, rather than being used by small family as intended, up to 20 people may share the same toilet. These toilets are instrumental in spreading disease, despite the messages chalked on cisterns encouraging users to keep the toilet clean.

Harare was once unique among African cities for having an exceptionally high number of flush toilets connected to a sewer network. Now, because of severe water cuts and low pressure, this toilet in Dzivaresekwa has no water. Instead grey water is reused and poured down as a flushing mechanism. And because of the growing populations in high-density areas, rather than being used by small family as intended, up to 20 people may share the same toilet. These toilets are instrumental in spreading disease, despite the messages chalked on cisterns encouraging users to keep the toilet clean.

Idle slides at Eastlea’s ‘Water Whirld’ wait for summer to re-open. According to the caretaker you could hire out Water Whirld for a party and they would fill the 55,000 litre pools from a borehole just for the day.

Idle slides at Eastlea’s ‘Water Whirld’ wait for summer to re-open. According to the caretaker you could hire out Water Whirld for a party and they would fill the 55,000 litre pools from a borehole just for the day.